Function of attribution

The referents treated in a proposition get certain predicates attributed to them and contract certain relations among each other. All these properties and relations accrue to them during the discourse. Concepts become more specific this way, referents get more highly individuated and ultimately pinned down to an individual.

Sometimes the speaker wants to narrow down a concept or to pin down a referent without asserting all those predicates needed to specify it. Attribution is the way to achieve this. At the functional level, the difference between predication and attribution consists in the fact that attribution does not commit the speaker to asserting the attribute of the referent; he may take this relation for granted. This was seen first and most clearly by H. Steinthal:

[Mens humana] quas cogitationes saepius tanquam subjectum et praedicatum una junxerat comprehensione, eas quamvis copulatione sublata arctius tamen denuo comprehensas tanquam unam sumsit cogitationem ad novamque cum aliis iunxit sententiam constituendam.

Inter has sententias: corona splendet et corona est splendida nullum fere cognoscitur discrimen. A quibus corona splendida non notione tanquam materia distinguitur, sed expressionis lingua effectae forma. Sed cum forma mutatur sensus. Nam illis sententiam enunciamus quam ab aliis probari volumus; sed verbis corona splendida rem exprimimus tanquam jam dudum judicatam ab omnibusque concessam, ita ut una habeatur composita notio. Enunciationis igitur unitas in notionis unitatem mutata est. (Steinthal 1847: 22, 74)

"The thoughts that the human mind has frequently joined as subject and predicate in one sentence, those, despite lifting their nexus [copula], yet uniting them again more tightly, he has taken as one sole thought and joined with others into the constitution of a new sentence."

"Between these sentences: the crown shines and the crown is shining, almost no difference is discerned. From these, shining crown differs not by the notion as some matter [the designatum], but by the form of the expression effectuated by language. With the form, however, the sense changes. For with those expressions we utter a sentence which we want to be approved of by others; but by the words shining crown, we express the thing as long decided and conceded by everybody, so that it is regarded as one composite notion. The unity of the sentence has, thus, changed into the unity of the notion." [literal and non-idiomatic translation, CL]

Modification

Modification is a subordinate predication applied to an argument that has a function in a higher proposition. The subordinate predicate is the modifier, the argument is the modified. Its being subordinate means that the modifier integrates into the syntagma of the modified. This is achieved by a particular kind of dependency.

Dependency

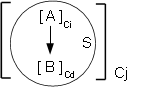

In the diagram, B, of category Cd, depends on A, of category Ci. Together they form the syntagma S, of category Cj. Now kinds of dependency may be defined by specific combinations of categories C. Modification may be defined as follows:

Cj is identical to Ci. Schematically: [ [ A ]Ci [ B ]Cd ]Ci.

This entails that S is endocentric, with A as its head. That is, elements of the category Cd may again combine with S, and the category of the resulting syntagma will again be Ci. In other words, B – or its category Cd – contributes nothing to the categorization of S (as Ci). This dependency relation is modification, where B modifies A. The potential of members of Cd to modify a member of Ci is a grammatical property of Cd, which may be reified as a modificative slot, similar to an argument place of a predicate.

In .a, the adverbial heavily modifies the verb works. In #b, the adjectival heavy modifies the common noun work. These are the two main kinds of modification. The former is adjunction, the latter is attribution. In other words, attribution is modification of a nominal expression.

| . | a. | Linda works heavily |

| b. | Linda's heavy work |

At the same time, hints at the paradigmatic (“transformational”) relationship between attribute and adjunct. In several languages (including Hixkaryana), there is one category of ‘adjective/adverb’.

Structural correlates

As is usual with grammatical operations, attribution has a semantic side as explained in §1. This is an effect needed in communication and cognition. And it has a structural side, which lends it an identity as a grammatical operation. As will be seen below, the semantic effect may be achieved without a dedicated operation. First of all, however, typical manifestations of attribution will be reviewed, with no claim to exhaustiveness.

Being a modifier, an attribute opens an argument position for the modified. For some categories, specifically for adjectives, this modificative slot is inherent in its members. Other adnominal dependents, including alienable possessive attributes, must be equipped with such a slot in order to function as a modifier.

Adjectival attribution

An adjective is a member of a word class whose primary function is attribution (Lehmann 2013). Consequently, adjectival attribution is typically not specifically coded. In English old town, the operation requires immediate prenominal placement of the adjectival; and that is all. In other languages, the order of attribute and head is variable. Then attribution may be coded by agreement of the attribute with its head, as in Latin erilis domus (master's:NOM.SG.F house:NOM.SG.F) = domus erilis ‘master's house’. Here sequential placement of the adjective contributes nothing to attribution, so the syntagma may even be discontinuous.

Another frequent attributive device is the attributor. This is a morpheme that signals the attributive function of what it combines with. In Mandarin, the formative de functions as a universal nominalizer: it converts anything into a nominal s.l. This may, thus, be used like an adjectival attribute. A prenominal attribute linked with the head by this formative appears in .

| . | bù | hǎo | de | lái-wǎng |

| Chin | [ NEG | good | AT ] | come-go |

| bad contacts | ||||

In Swahili, the postnominal attribute agrees with the head in noun class, as illustrated by .1

| . | a. | ki-kapu | ki-kubwa | ki-moja |

| Swahili | CL7-basket | CL7-large | CL7-one | |

| one large basket | ||||

| b. | vi-kapu | vi-kubwa | vi-tatu | |

| CL8-basket | CL8-large | CL8-three | ||

| three large baskets | (Welmers 1973:171) | |||

Nominal attribution

Here we are talking about a construction in which a nominal head is specified by a dependent NP. No appropriate term for this construction is established. The traditional term ‘genitive attribution’ presupposes a genitive on the attribute, which is present in some languages, including Korean as illustrated by and , and absent from others. The term ‘possessive attribute’ presupposes a possessive relationship between the dependent and the head, which is absent in several subtypes of the construction, including below. The term ‘nominal attribution’ might be good if it were clear enough that the epitheton nominal refers to the attribute, not to the head (which is nominal by definition in just any attribution).

The dependent in this construction is an NP. A naked NP does not by itself modify anything. One of the devices to convert an NP into an attribute is, again, the nominalizer, which here functions as an attributor, as in (cp. with ).

| . | gè | rén | de | xīn |

| Chin | [ CL.HUM | person | NR ] | heart |

| everybody's heart | ||||

A common device that lends an NP an adnominal modificative slot is the genitive, as in f.

| . | hankuk-ʉi | munhwa |

| Kor | Korea-GEN | culture |

| Korea's culture | ||

| . | cɵ | cip(-ʉi) | cipung |

| Kor | D2 | house(-GEN) | roof |

| roof of the house | |||

| . | kʉ | cip | twi |

| Kor | D3 | house | back |

| back of the house | |||

Instead of modifying something, an NP may also be governed by its head. In this situation, it needs no case. This is why no genitive appears on cip in : the head noun is relational. In Korean, some nouns such as cipung in allow both variants of adnominal nominal dependency.

Nominal relationality is not grammaticalized in the form of an alienability distinction in adnominal nominal dependency of SAE languages. The term ‘attribution’ is applied indistinctly to all three construction of – . Given, however, the fact that a dependent of a relational noun is not a modifier, but a complement, relationships such as the one of , i.e., inalienable nominal constructions, should probably not come under attribution.

Swahili nominal attribution combines the strategies of the attributor and of agreement: The postnominal attribute is introduced by an attributor, and this agrees with the head in noun class, just like an adjectival attribute. Compare with .

| . | a. | ki-su | ch-a | Hamisi |

| Swahili | CL7-knife | CL7-AT | Hamisi | |

| Hamisi's knife | ||||

| b. | ny-umba | y-a | m-tu | yu-le | |

| CL9-house | CL9-AT | CL1-man | CL1-that | ||

| that person's house | (Welmers 1973:275) | ||||

Clausal attributes

Similarly as a noun phrase, a plain clause does not by itself function as a modifier, as all of its argument (and other) places are occupied. There are essentially two ways in which a proposition may specify a nominal concept:

- The proposition may be left intact, thus designating a situation which may specify a head with an abstract meaning. Structurally, this may require that the clause be provided by an attributor which combines it with its nominal head. Such a nominalized clause is an adnominal substantive clause.

- The proposition may be oriented towards one of its components. Such a nominalized clause is a relative clause.

Adnominal substantive clause

Since a substantive clause belongs to the category NP, it does not by itself modify anything. Nor is it particularly necessary to combine it with a nominal head, since this could essentially only be an abstract noun, thus a hyperonym of the meaning of the substantive clause. If such a construction is needed nevertheless, a common strategy of combining the clause with a nominal head is apposition rather than attribution. shows a subordinate clause in the function of apposition to a head noun.

| . | The [ fact [ that appositions are not marked ] ]Nom makes them hard to identify. |

The subordinate clause of looks like a complement clause in this language. However, it is not governed by its head noun. The semantic relation is of an explicative nature. This is a relation that in various languages may be expressed by a genitivus explicativus. And in fact, the Spanish translation of does show something of the sort:

| . | El [ hecho [ de que las aposiciones no llevan marca ] ]Nom las hace difíciles de identificar. |

In , the subordinate clause is attached to the head noun by the same preposition de which otherwise attaches a genitive attribute to a head nominal. Consequently, the inner brackets in clearly enclose a modifier.

Theoretically, an adnominal substantive clause could be governed by a relational head noun. Consider .

| . | Your claim [ that nouns may take clausal complements ] disturbs me. |

Claim is here either an action noun or a nomen acti, based on the transitive verb claim. Given this, its undergoer argument position might be conserved under nominalization, and the dependent clause in might be occupying it. This may be the case for a deverbal abstract noun in this function, as in you claim her innocence vs. your claim of her innocence. However, the relationship of the subordinate clause of to its head is structurally appositive and, semantically, explicative.

Like complement clauses, adnominal substantive clauses can be classified by their sentence type. shows an adnominal interrogative clause, and shows an adnominal jussive clause.

| . | The question of [ why heavenly bodies are globes ] has a straightforward answer. |

| . | The order [ that Linda leave the country ] came too late. |

Attribution of the relative clause

If an oriented clause combines as a modifier with a head nominal, it is an (adnominal) relative clause. There is an entire section devoted to relative constructions. The positional types of the relative clause bear diverse relationships to the operation of attribution:

- In the adnominal relative construction, the relative clause is an attribute to the head nominal.

- In the internal-head relative construction, a core of the complex concept is formed, which the rest of the relative clause is understood as specifying.

- The postposed relative clause provides what is semantically an attribute to the head, while the operation itself may not be coded.

These three cases are discussed in turn.

Attribution of the adnominal relative clause

In many languages, the relative clause combines with its head in an asyndetic construction. This is true both of the prenominal relative clause in and of its English postnominal counterpart.

| . | kore-wa | ano | hito-ga | kai-ta | hon | desu |

| Jap | D1-TOP | [ D3 | person | write-PST ] | book | COP |

| This is the book that person wrote. | (Andrews 1975:46) | |||||

Alternatively, the relative clause may combine with its head by means of an attributor. In Mandarin, the nominalizer de converts non-nominal syntagmas into nominal ones. With nominal attributes, it functions as an attributor; with other attributes, this is an implicit secondary function ().

| . | wǒ | bǎ | nǐ | gěi | wǒ | de | shū | diūdiào-le |

| Chin | I | ACC | [you | give | I | NR] | book | lose-PRF |

| I lost the book that you gave me. | ||||||||

Agreement of the relative clause with its head may also be found. In , the relative clause agrees with its head in case.

| . | Yibi | yaṛa-ŋgu | njalŋga-ŋgu | djilwa--ŋu-ru | buṛa-n. |

| Dyirbal | woman | man-ERG | [ child-ERG | kick-REL]-ERG | see-REAL |

| The man the child had kicked saw the woman. | (Dixon 1972) | ||||

A full-fledged relative pronoun may agree with its head in categories like gender and number. The relative pronoun in does so, while the cases differ because the syntactic function of the relativized position differs from the syntactic function of the complex nominal in its matrix.

| . | non | eos | homines | qui | populum | concitarant |

| Latin | not | ANA:ACC.PL.M | man:ACC.PL | [ REL:NOM.PL.M | people:ACC.SG | excite:PLUPRF:3.PL ] |

| consulum | litteris | evocandos | curare | oportuit? | ||

| consul:GEN.PL | letter:ABL.PL | summon:GERUND:ACC.PL.M | care:INF | necessary:PERF.3.SG | ||

| Ought you not to have taken care that those men who had excited the populace should be summoned by letters of the consuls? | (Cic. Verr. 2, 1, 84) | |||||

It is here not the relative clause but only the relative pronoun which agrees with the head. Still, since the relative pronoun has further constitutive functions in relative-clause formation, in particular the subordination of the relative clause, its agreement signals the attributive function of the relative clause.

Adnominal substantive clause vs. relative clause

It remains to clarify the distinction between an adnominal relative clauses and an adnominal substantive clause. By definition, the difference consists in that the relative clause is oriented towards the same entity designated by the head nominal, whereas the substantive clause is a plain (thus, non-oriented) clause. The semantic consequence is that the entity named by the head nominal has a semantic function in the relative clause, which is not the case for an adnominal substantive clause.

| . | a. | The fact [ that we have ignored so long ] is now our doom. |

| b. | The fact [ that we have ignored Linda so long ] is now our doom. |

In .a, the referent designated by fact plays the role of undergoer inside the dependent clause, as may be proved by the appropriateness of the paraphrase ‘we have ignored this fact so long’. The adnominal clause of .a therefore is a relative clause. In #b, the same referent plays no role inside the dependent clause. On the contrary, the position of the undergoer there is occupied by Linda. This is therefore a substantive clause.

Depending on the structure of the language, a given construction may be ambiguous between a relative construction and an adnominal substantive clause construction.

| . | The fact [ that we are liable to forget in the rush of events ] a) is the following / b) is part of our human nature. |

In the relative-clause reading of , the verb forget is transitive, and continuation #a is more natural. In the adnominal substantive clause reading, forget is intransitive, and continuation #b is more natural. An analogous ambiguity is possible with dependent interrogative clauses, as in .

| . | Die | Frage | [ welche | ich | lösen | soll ] | ist | schwierig. |

| German | DEF:F.SG | question(F) | which:F.SG | I.NOM | solve:INF | should | be:PRS.3.SG | difficult |

| The question a) that I am to solve / b) of which one I am to solve is difficult. | ||||||||

German has a relative pronoun which is identical with an interrogative pronoun and which appears in . The adnominal substantive clause is appositive and consequently not marked as such. The pronoun might take up the head noun Frage. Then it is a relative pronoun, the construction is a relative construction, and reading #a results. However, the pronoun might also be an attribute to a zero anaphor taking up some antecedent mentioned in some preceding sentence (e.g. a task). Then the pronoun is an interrogative pronoun, the dependent clause is a subordinate interrogative clause, and reading #b results. (The two readings differ in their intonation, since an interrogative pronoun, but not a relative pronoun, may bear focus stress.)

Attribution of the internal-head relative clause

Since the nucleus has a semantic function and a syntactic function as a nominal component of the clause, the latter cannot, at the same time, literally be its attribute. However, the semantic effect of attribution may be obtained, nevertheless. First, the correlative diptych will be considered. Here the internal head is accompanied by a relative pronoun, as shown by .

| . | ab | arbore | abs | terra | pulli | qui | nascentur, |

| Latin | [ from | tree:ABL.SG | from | earth:ABL.SG | sprout(M):NOM.PL | REL:NOM.PL.M | be.born:FUT.3.PL ] |

| the sprouts that will rise from the tree from the earth, | |||||||

| eos | in | terram | deprimito. | ||

| 3.PL.M | in | earth:ACC.SG | push.down:IMP | ||

| those you will push back down into the earth | (Cat. agr. 51) | ||||

The relative pronoun identifies the head, both by agreeing with it and by its default adjacent position. This triggers a series of semantic operations:

- The head concept is taken out of the proposition.

- This leaves an empty place in the proposition.

- The proposition is oriented towards the empty position.

- The oriented proposition is interpreted as an attribute to its head.

The semantic effect of this complex strategy is an equivalent of attribution proper.

In the variety of the preposed relative clause which does not mark the head by any structural device, the semantics of concept anchoring is, nevertheless, not much different.

| . | yankiri-ḷi | kutja-lpa | ŋapa | ŋa-ṇu, | ŋatjulu-ḷu | ∅-ṇa | pantu-ṇu |

| Walb | [ emu-ERG | SR-PROG | water | drink-PST ] | I-ERG | AUX-SBJ.1 | spear-PST |

| The emu which was drinking water, I speared it. / While the emu was drinking water, I speared it. | (Hale 1976:78) | ||||||

The first clause of is just a neutral subordinate clause. Nevertheless, what is predicated on the referents mentioned accrues to them as information characterizing them. Depending on the context, this may serve to distinguish the referent in question from others of the same species. The zero anaphor of the subsequent main clause takes up the referent thus specified in the subordinate clause. The semantic effect is, thus, the same as in the correlative diptych. The relevant difference from the latter consists in the fact that the relative pronoun forces an interpretation as relative construction, while this does not happen in the neutral adjoined clause. has the same structure as , and here an interpretation as relative construction is excluded, because there is no anaphora.

| . | kutja-ka-lu | yuwali | ŋanti-ṇi | tjuḷpu | panu-kaṛi-ḷi | kankaḷu | watiya-ḷa, |

| Walb | [SR-PRS-SBJ.3.PL | nest | build-PRS | bird | many-others-ERG | up | tree-LOC] |

| Whereas many other birds build a nest up in the tree, | |||||||

| maṇa-ŋka | ka-njanu | tjinjtjiwaṇu-ḷu | ŋanti-ṇi | yutjuku-paḍu. | ||

| spinifex-LOC | PRS-REFL | jinjiwarnu-ERG | build-PRS | shelter-DIMIN | ||

| the jinjiwarnu [bird species] builds itself a small shelter in the spinifex grass. | (Hale 1976:87) | |||||

One may therefore doubt whether should be considered a relative construction. It marks the transition between an all-purpose subordinate clause and a relative clause.

The circumnominal relative clause differs from the preposed one by its embedding.

| . | (shí) | łééchą́ą́'í | b-á | hashtaal-ígíí | nahal'in. |

| Navajo | [ I | dog | 3-for | IMPF:1:sing-NR ] | IMPF:3:bark |

| The dog that I am singing for is barking. | (Platero 1974, (40)) | ||||

Here, too, an internal head is formed on a semantic basis, viz. by the selection restrictions imposed by the matrix verb. Once the noun ‘dog’ is the core, the rest of the clause is interpreted as specifying it.

Attribution of the postposed relative clause

The case of the postposed relative clause is similar. In the correlative-diptych variety, the relative pronoun in the second clause refers back to a nominal constituent of the first clause which by this anaphora gets identified, ex post, as the nucleus of the developing relative construction. By the anaphora, the information contained in the subordinate clause would, in any case, accrue on the referent previously established. In cases such as , however, this is not only additional information on an already identified referent, but instead is necessary to identify the referent meant. Thus, this is an unmistakable restrictive relative construction; the postposed relative clause is an - albeit distantiated - attribute to the head.

| . | ek | d' | éthore | klêros | kunéēs |

| Greeek | out | however | AOR:leap:3.SG | ticket:NOM.SG.M | helmet:GEN.SG.F |

| Out leapt from the helmet that ticket | |||||

| hòn | ár' | ḗthelon | autoí | |

| [ REL:ACC.SG.M | PTL | AOR:wish:3.PL | 3.NOM.PL.M ] | |

| which they had wished. | (Hom. Il. 7, 181) | |||

If there is no relative pronoun, as in , the attribution ex post remains entirely implicit.

| . | ŋatjulu-ḷu | ∅-ṇa | yankiri | pantu-ṇu, | kutja-lpa | ŋapa | ŋa-ṇu |

| Walb | I-ERG | AUX-SBJ.1 | emu | spear-PST | [ SR-PROG | water | drink-PST ] |

| I speared the emu which / while it was drinking water. | (Hale 1976:78) | ||||||

As before, the postposed subordinate clause gives additional information on an entity introduced in the main clause. Possibly nothing else happens; and then the subordinate clause is no attribute to the antecedent in the preceding clause. However, it is possible that the subordinate clause specifies the referent meant. In this case, it would be an attribute ex post, although not marked as such.

1 Bantu noun classes combine class proper and number, such that class 8 is the plural of class 7.